And women more so than men.

The whole history of fiction shows that alternative realities are an attractive and profitable idea. So back in the 1990s, when electronics had arrived at a point where people could build headsets that blocked off actual reality and replaced it with a virtual version created inside a computer, it looked as if something world-changing might have arrived. Games companies were particularly excited, and Nintendo, Sega and Virtuality duly piled in.

The world, however, stubbornly refused to be changed. It might have put up with the low-resolution images, the choppy scene transitions and the poor controls, for these would surely have got better. It might also have put up with the price (the headsets in question could cost up to $70,000), for that would surely have come down. It could not, though, accommodate the dizziness, nausea, eye strain, vomiting, headaches, sweating and disorientation that many of the technology’s users (more than 60%, according to one study) complained of—a set of symptoms that, collectively, have come to be called “cyber-sickness”. Though not fatal to people, cyber-sickness certainly helped damage the industry, which more or less vanished.

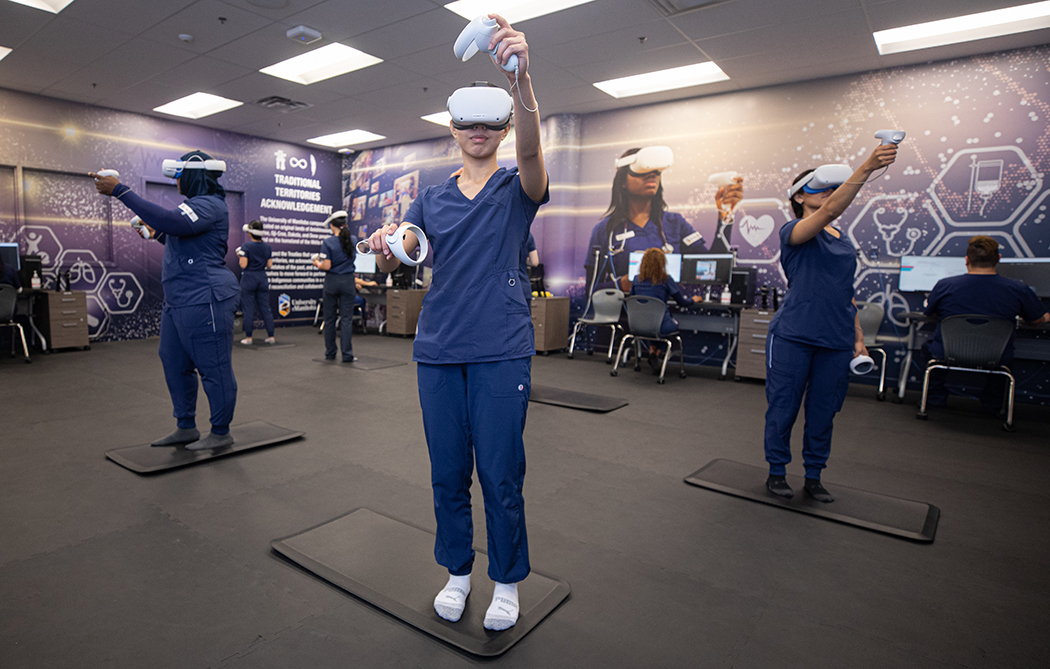

Two decades later, however, virtual reality (vr) returned from the dead, with better images, smoother transitions and more precise controls. There were also applications beyond games. The upgraded technology has found use in social media, interior design, job training and even pain management. Moreover, a new set of companies, Oculus (now part of Facebook), htc and Sony, have come up with products that do not require a second mortgage to afford.

Despite these improvements, though, vr has not lived up to expectations. It has done respectably, with sales in 2018 of $3.6bn, according to SuperData Research, a market research firm. But that is only 2.4% of the global market for games. Many people—and not just the usual hypesters—thought that this time around vr would become a blockbuster technology. It has not happened. Part of the reason is that cyber-sickness has not gone away. One study suggests between 25% and 40% of users still experience it.

Dealing with this is difficult, not least because there is an argument about what triggers it in the first place. Two theories dominate. One is that users experience sensory conflict—a mismatch between what they see and what their other senses and their real-world knowledge tell them they should be experiencing. The other is that the underlying cause is individuals’ inability to control their bodies and maintain proper posture when moving around in virtual environments. To complicate matters, both hypotheses could be true.

Feeling woozy

Sensory conflict there certainly is. For example, when users move their heads they expect what they see to change immediately in response. But time-lags and poor graphics mean their visual input often fails to meet the brain’s expectations. Dealing with this means increasing the “frame rate” at which the virtual world is presented to a user, improving the resolution of the images and reducing the latency of response to a user’s movements. All of these require clever processing by the computer responsible for creating the illusion.

Improvements in tracking what a user is doing also help. “Room scale” vr systems let people move around in the real world while perceiving similar movement in the virtual one. Following a user’s movement can be done in one of two ways. Outside-in tracking relies on external cameras observing beacons of various sorts scattered around a user’s body. Inside-out tracking is the opposite: the beacons are scattered around the room and detectors on a user’s body employ them as reference points.

On top of all this, there is the design of the lenses that sit inside a headset in front of a user’s eyes to adjust optically for the fact that what is actually a nearby image is supposed to be some distance away. Since the shape of these lenses is fixed and the amount of adjustment required varies with what is being looked at, distortion is inevitable. But distortions are particularly noticeable when users move their eyes, says Paul MacNeilage of the University of Nevada, Reno. Some headsets therefore now track a user’s gaze and move the lenses within the headset in response.

Make the input too credible, though, and you run into a different problem—the contrast between what a user’s eyes are seeing and what the motion-sensors in his inner ear are detecting. To deal with that, some designers program in a “virtual nose”, just visible to the user, to serve as a point of reference.

These tactics help. But they do not get rid of cyber-sickness entirely. That is where the second hypothesis, unstable posture, comes in. And it is one that has the virtue of offering an explanation of a mystery about the condition—why women are more likely to be affected than men.

Thomas Stoffregen of the University of Minnesota, who has studied the matter and found women four times as susceptible as men, cites the example of driving a car to explain the unstable-posture hypothesis. When turning the steering wheel, he observes, drivers need to keep their heads oriented to the road. They need to stabilise their bodies, particularly when the car is changing direction and pushing the body in different ways. “When you spend a lot of time in cars, you get used to doing that,” he says. “It’s a skill.” But in virtual environments, where there are no forces to act as signals, people have not learned to adjust their bodies properly. They lean when the virtual car turns, but in fact they are leaning away from stability. He finds this particularly affects women, who have lower centres of gravity than men. That may cause them to sway more. And increased swaying, he has found, correlates with higher rates of cyber-sickness.

It is a neat idea. But Bas Rok.ers of the University of Wisconsin-Madison believes there is a simpler explanation for women’s experience of cyber-sickness, which is that headsets are not designed for them. For vr to work properly, sets need to be adjusted to the distance between the pupils of a user’s eyes. In one popular brand, however, Dr Rokers found that 90% of women have an interpupillary distance less than the default headset setting, and 27% of women’s eyes do not fit the headset at all.

If Dr Rokers is correct, a big part of the problem of cyber-sickness might be dealt with by a small change to helmet design. If women’s rates of the complaint could be reduced to the level experienced by men, then a lot more people could enjoy vr rather than enduring it. And then, perhaps, it really might achieve its potential.

Quelle:

https://vrroom.buzz/vr-news/tech/cyber-sickness-still-challenge-vr